15 Minute Rule - The Horsemen

There's been a lot of talk about the state of current horror films being largely built around meaningless scenes of bodies being torn about. When that talk turns to WHY modern horror has gone in this direction you get a lot of the typical old saws (if you'll pardon the pun) about the decline of society and civility, the loss of morals, the lack of imagination.

None of these arguments ever held much weight for me. Firstly, as much as all these flicks get their jollies off of gore and dismemberment, I don't know that ONE of them has topped some of the prime 70s gore flicks. Secondly, people have been making those same arguments about various incarnations of horror for years, but I think there is something particularly different about this current era of horror film that seperates it from what's come before. I'd never been able to put my finger on it, but now that I've seen The Horsemen, I think I've got a theory:

We're not afraid of anything anymore.

I can hear some of you scoffing from here. "We live in a time of fear!" you're yelling at me through your monitor. "Fear has been the primary emotion of the past decade!" "Two words: 'Fox News'" "I'm afraid RIGHT NOW!"

Yeah yeah yeah, sure, but listen: What are you REALLY afraid of? Honestly? We talk about being afraid of global warming or terrorism or school violence or economic collapse, but are we really afraid of these things? How much do we really think about them? How much do they guide our actions? How much do we take precaution against them? How much do we sacrifice for them? How much do we actively engage with them? OK, OK, I don't mean to jump on you, dear readers, but in the broad cultural sense, I just don't know that there's as much actual FEAR out there as we've been led to believe.

I think there are two things necessary for fear: An element of the unknown and a lack of control. I think nowadays people think we know everything and that we've got stuff pretty much under control. When people talk about things getting "out of control" now, what they really mean is that things aren't going their way, and if people just did what they wanted, everything would be fine. That's not "out of control," that's "out of MY control until I can wrestle that control back."

My good friend Polly Frost is fascinated by disappearance cases. There's more than you'd think, she tells me, mostly young people, mostly women, who are last seen getting into cars with strangers, or walking off drunk into the night by themselves or going down to Mexico and evaporating into the haze of crazy parties. They put up information on public websites detailing where they are, where they'll be, when they're leaving and if they're alone. "These people don't think anything could POSSIBLY happen to them!" she explains to me. They're not afraid. Who is?

This is deadly for horror movies. I don't believe you can make a scary movie unless you yourself are, in some way, scared. Horror movies examine what scares us, and if nothing scares us then all our horror movies can be are remixes of other scare flicks.

And it seems to me, in the same way the prat fall or the fart joke is the baseline for comedy, intense physical bodily harm is the baseline for horror. If you aren't afraid of unknown forces, mental illness, repressed animalistic tendencies, God, predestination, moral failings, karmic retributions, sexual failings, judgment, apocalypse or any of the genre's other many cornerstones upon which the horrors build, really the only thing that's left to you is getting torn apart. In a society that's possibly become narcissistic and onanistic, where nothing of consequence exists outside of the self, the only thing to fear is something explicitly harming the self. Which I suppose may be a lack of imagination, or at least abstract thinking. The only thing these guys can possibly imagine as being horrifying is the fairly unlikely event of getting kidnapped by a deranged killer who enjoys setting up Rube Goldberg death machines for amusement and instruction.

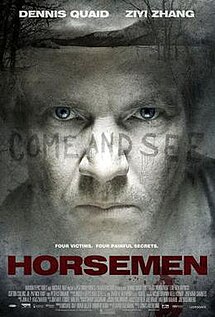

What got me thinking about this regarding the 2009 Jonas Akerlund film "The Horsemen" is the title itself. The titular horsemen are the Biblical four horsemen of the apocalypse. Within the film a group of murders are accompanied with the phrase "Come and see" written around the corpses, pointing the intrepid detective Dennis Quaid to the verse in Revelations detailing the End Times arrival of Death, Famine, Disease and War. What could the killer possibly be thinking, quoting this verse? What kind of connection are they trying to draw to themselves and these scriptural harbingers of doom?

Not much of one. The ending, which I'm going to spoil for you here, as the greatest "spoiling" of all would be to actually watch the garbage, involves Dennis Quaid's son revealing to Quaid that he was part of a collection of kids whose families didn't treat them right, so they've decided to go about viciously murdering them, bringing about the END TIMES of mommies and daddies not doling out enough hugs (or too many, in the case of Ziyi Zhang and her adopted father, a criminally wasted Peter Stormare). There is so much spectacularly wrong with this that I'm not going to go into it in detail, but instead provide a Top Ten list of biggest idiocies:

1) To complain that his dad didn't pay enough attention to him and got all withdrawn after is wife DIED OF CANCER, the son attempts suicide in a fantastically grotesque fashion while having his father watch, which will certainly teach him a lesson and is totally morally equivalent.

2) Also, in doing so he's leaving his younger brother without his support...

3) ...And with a dad who not only lost a wife to cancer, but watched his son hang himself by meathooks and drown in his own blood.

4) Did I mention the kid hangs himself with meathooks? By himself? Which is so impressive, it's impossible.

5) The kid attempts to drown himself through puncturing his lungs, which happens earlier in the film but is executed by someone with medical training. Not some jerky kid. And then he wonders why it isn't working.

6) Also, when did he puncture his lungs? Before or after he hung himself up on meathooks?

7) The kids committing these murders are broadcasting them out to a whole online community of kids who think their parents are jerks and who have all managed to keep this whole thing entirely under their hats and off any FBI watchlist this whole time.

8) Some of the kids kill one of the abusers, some of them kill themselves while making the person who mistreated them watch. For kids who sat together and planned out a bunch of extremely complex and involved murders, it's weird they didn't try to talk their friends out of killing themselves. OR maybe talk the other friend INTO killing theirself. That seems like a weirdly crucial point of the plan to have a disagreement about.

9) The movie actually seems to AGREE with the kid. If we painted him as super-crazy and deranged, that'd be one thing, but the movie seems to be tsk tsking at Quaid's poor parental skills right along with him. Also, the kid's a teenager and at one point complains that Quaid would have realized his plan if he'd ever actually GONE INTO HIS ROOM like a good helicopter parent should, which may be the first time I've ever seen a teenager complain that his parent has given him TOO MUCH privacy.

10) The kid is quoting scripture while doing this, and we see him in church and sort of get a hint that his beloved mother was very religious, which makes this whole course of action seem a little...problematic as far as his belief structure goes.

It's this last point I really want to address. The title of the movie references a Bible verse. We have scenes of the family in church and a few scenes involving Bibles around the house. The main psychopath quotes scripture. But never for one minute do I think anyone in this movie or anyone involved in this movie has any actual Biblical belief, or even any actual interest other than that some verses in Revalations sound real spooky and crap.

I don't think you have to be religious to make religious horror, but I certainly think it helps. And even if you're not, you have to at least take it seriuosly within the world in which it's existing or with the characters who take it seriously enough to act on it. Being religious myself, my love of religious horror is probably what kept me watching this piece of drivel well longer than I should have. I kept hoping, waiting for some moment where they might actually take their own words seriously, where any of this might pay off. Nada.

And then I got to thinking, what horror movies in the last twenty years or so used religion and ACTUALLY took it seriously? The only movie that came to mind was the Exorcism of Emily Rose, which I love. AH, and Red State, which I also kinda loved. But that's about it. I can name you a bunch of movies that use demons, exorcisms, priests and devils, but not a one of them is actually invested in them or what they represent. They aren't even using the religious trappings to SAY anything, or even make it a metaphor for something else. They're just using it as window dressing. They're as scared of or by it as they would be of a rubber spider.

It's not just that they don't find religion scary, I don't think they find teenage alienation or the numbing effects of grief or any of the other possible themes you could pull from the film scary, either. They just think some of the images look cool and that hanging people up from meathooks and self-evisceration is INTENSE and everyone kinda wants to play martyr in front of their parents at some point. Essentially this is the horror movie version of that scene in A Christmas Carol where Ralphie imagines going blind from soap poisoning. And just about as scary.

Why make a horror movie of something you don't find scary? That's like making a comedy full of jokes you don't find funny, or a thriller with set pieces free of intensity or rising action, but I feel like that's pretty much every damn horror movie I see. If I could make one plea to any horror filmmakers out there, I suppose it would be this: Before you try and scare me you should at least be able to scare yourself.

Film Review #1 - Cloud Atlas

Cloud Atlas: Everything is connected! Probably to something ridiculous!

I remember, even when I was a kid, thinking it strange in movies, usually from the 80s, when young, upstart kids yelled at their dreamless, dead-inside parents that they'll never be like them, they'll never be losers who, gasp, WORK IN A FACTORY. Was it really so terrible to work in a factory? I mean, come on, it was the 80s. It's not like this was Dickensian London and children were working in clothing mills for 20 hours a day and making pennies. These people were adults, probably union, they had eight or nine hour shifts they pulled, got paid more for overtime and holidays, and they did their jobs and then came home and lived their lives. What was so terrible about that? What was the alternative that these children dreamed of? A future where everyone was either a businessman/entrepreneur or an artist? I guess that's nice and all, but in that future, who'd make all the stuff?

China, apparently. Whoops.

Even from an early age I always wondered why some things were so generally poo-pooed. Another thing I never understood is why fun, entertaining art that's made largely to be enjoyable is less worthwhile than something that takes itself entirely seriously. It's hard to make truly memorable and remarkable flights of fantasy and whimsy, to do so is a great achievement, surely as great as making something that makes the viewer consider their own mortality in quiet terror. I'd even possibly argue moreso.

Which leads us to the Wachowskis. From day one they've always been better showmen than thinkers, but they seem to constantly yearn to shake off their magician's cape and don an academic's robe. I'm in the minority on the Wachowskis as I wasn't even a fan of the first "Matrix" film and I think their best movie by far is the much-reviled "Speed Racer," but even so most agree the last two "Matrix" films were abysmal, largely due to their self-serious tone, meaningless philosophizing, hackneyed allegories and the overly effects-laden action sequences that caused the supposedly dramatic confrontations to feel weightless and flimsy (I'd argue that the first one had nearly all of these problems, but perhaps that's for another time).

And so now "Cloud Atlas," a thoughtful film that dares to ask the tough philosophical questions like "Is racism bad?" "Should women be viewed as equal to men?" "Should homosexuals be persecuted and reviled?" "Should we lock up old people who annoy us in prison-like nursing homes?" and "Is it OK for a government to enslave an entire caste of people and turn them into food?" I'm no Wachowskian mystical native shaman seer, but I'll bet I can probably guess your, and nearly every other person's, response to those questions.

Of course, that's not all the movie is about. It also explores how everyone is connected and we are all part of the great cosmic fabric of humanity. Unless, of course, we work for an energy company. Or are an 18th century businessman. Or a bigot or racist in an era where bigotry and racism were the norm. Or wear crazy face paint. Or are an art critic. For a movie that seems to celebrate the one-ness and communal nature of humanity, it sure does take a lot of glee in murdering a number of people. I haven't seen such an exuberant extinguishing of a critic since The Lady in the Water.

The Wachowskis so desperately want to be philosophical filmmakers, but one of the central elements of philosophy is a continuously-questioning mindset, and the Wachowskis are so overly eager to tell you the answers that there are barely even any questions at all.

Let me provide an example. In the story that takes place the farthest in the future Tom Hanks plays a tribesman who hides in fear while a group of savages attack and murder his brother-in-law and nephew. It's a terrible event, but it is played to make the Hanks character out to be a coward. I suppose, but he was also grossly outnumbered and only had a knife while the numerous marauders were armed with crossbows and swords. Is it cowardice to not openly walk into certain death in a vain attempt to save a loved one? That's actually a philosophical question, but that's not really what the piece is asking.

No, instead there's some other gobbledygook about sending out a signal to get space people to come down and help them, and THEN we get to the big conclusion. While Hanks is out activating the space signal his village is attacked by the savages. Hanks returns too late, all are dead except his young niece, who hid (was SHE a coward?). Hanks then finds a sleeping savage. Throughout this piece Hanks has a bad angel who appears and tells him to do the savage, cowardly thing. Occasionally he hears a good angelic voice speak out to him. In this moment the good voice tells him not to kill the savage. He kills the savage anyways.

Now I'm interested. A group of savages come back and notice their missing brother. Hanks again can't kill them all, so he runs. They give chase. Hanks makes it back to the spot where his brother-in-law was killed. I wondered, are the filmmakers actually going to kill him as punishment for his cowardice? Will he somehow overcome the savages by becoming as savage as they are? Will these savages spare him, throwing doubt and uncertainty on the roles he had assigned both them and himself?

Nope. Halle Berry shows up with a laser gun and kills them all. Then he, Berry and the niece go off to meet the nice space people because they are the winners and the good guys and the nasty, face-painted people were evil and gross and deserved death. They'd have worn black hats if they wore hats. Oh, wait, the evil angel that taunts Hanks and has a painted face similar to the savages actually DOES wear a black hat. Well, I guess that's wrapped up all tidy then. PHILOSOPHY!

The one solid section of the piece is, quite tellingly, also the funniest. "The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish" has Jim Broadbent playing the titular Timothy, a sad-sack failed literary agent who comes into serious dough when a client of his, a street tough-turned writer, throws a critic off a high balcony to his death, sending sales skyrocketing. The tough goes to jail, Cavendish makes some serious cash and all is well until the tough's relatives come looking for what they see as their share. When Cavendish discovers he has nowhere near the money these ruffians want, he runs away to his more successful brother, who sends him to what he thinks is a hotel, but is actually a sanitarium.

As opposed to the Hanks character, Cavendish is an out-and-out coward, hiding a secret yet trivial affair with his brother's wife, running from the thugs and, most importantly, abandoning the love of his life at a young age when her parents offered resistance. He is also a scheister who is making hefty profits off of a man's horrific demise.

He is, in essence, an interesting and flawed character. Consequently, when he does do something heroic later in the movie, it means something. It's a real turning point for the character. It works.

There are parts of the Cavendish segment that don't work, or collapse under the weight of too much (which is to say, practically any) thought, but it's easy to forgive because it's a fun, silly segment and they're not asking us to consider these things. Not so in the other sections, where this kind of thoughtlessness can be deadly. Let's do a compare and contrast involving the police, or lack thereof.

In the Cavendish segment, when the ruffians come to harass Broadbent, they tell him not to go to the police because it would be useless since the police couldn't do anything to save the critic their bro murdered. Well, sure, but that falls apart pretty quickly when you think for two seconds about the extraordinarily different scenarios of a man deciding in an impromptu moment to throw another man off a balcony versus a group of known thugs whose associate recently murdered a man with little provocation making explicit threats and extortions on a 24 hour timetable. I don't know precisely how much the police could do, but I'd say it'd be worth giving them a call. They could certainly do more than they did for the critic, simply given the nature of time (something this movie has invested heavily in).

But no matter. The piece is fun and not calling the cops moves Cavendish to the sanitarium quicker and la di da. Now let's look at the section entitled "Half Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery."

In this story Halle Berry plays a sassy female reporter in the 70s, which means you get a lot of real heavy-handed references to pot, 70s rock, nuclear energy, the Feminist movement, the Sexual Revolution and anything else that is Seventies with a capital S. She's investigating an energy scandal that puts her in the sites of a professional hitman. This leads to what must certainly rank as one of the worst plans in all of cinema history.

Keith David, who works for the energy concern that's put the hit out on Halle Berry but who isn't one of the bad guys, probably because he's ethnic (more on that later), comes to save Halle Berry from this hitman who has managed to successfully eliminate a number of people through some pretty explicit and brutal means. No quiet poisons or fake accidents for this guy. We're talking bullets to the head, bombs on planes kind of stuff. So Keith David's plan is to...let Halle Berry walk down the street where they know the hit is going to happen and Keith David's going to...ram into the guy's car. That's it. A professional killer, an expert marksman and one would have to think probably a pretty skilled evasive driver, and your plan is to put Halle Berry in the middle of broad daylight and hope that you sideswipe the guy well enough to...kill him? Make him reconsider his ways? David's maneuver goes off in a way where we're supposed to think something went awry and the tension is supposed to ramp up, but honestly, what results were they hoping for? It seems to me this was absolutely the best result they could have reasonably expected.

Outside of, you know, going to the police with a metric crap ton of evidence. There is always that option. When a character like Cavendish makes this kind of error in the kind of story he tells, it's all part of the whimsy and the fun. He's a magoo! Of course he'd do something like that. But when you're telling a story about the serious corrupting dangers of corporate power turning men against men, it's...well, it's a bit silly, is what it is.

Even their visual motifs work better in comedy. Take, for instance, the gimmick where different heroes in each timeline have this comet birthmark. It's treated as a big revelation each time, but, honestly, what does it mean? At best it's an inane and simplistic visual representation of the whole "we are all connected" cheesy philosophy. At worst it points to a somewhat fatalistic determinism, a sort of reverse mark of Cain. The good are marked from birth to be the harbingers of the best of humanity, others are doomed, markless, to be painted cannibals, slave traders or, worst of all, businessmen.

You know where a similar premise worked to greater effect, both for entertainment AND philosophical examination? The Coen's film "Raising Arizona." In the climactic fight of the film, Nicholas Cage's H.I. McDunnough is grappling with Randall Cobb's Leonard Smalls. Throughout the movie the Coens have been toying with the idea of what makes up an outlaw, and nowhere is there examination clearer than in Cage's skinny, hapless, loving and lovable H.I., a criminal, being beaten and abused by the grotesque, hate-filled "warthog from Hell" Leonard, a man ostensibly on the right side of justice and the law. At the fight's madcap apex, H.I. and Leonard make the startling discovery that they both share the same Woody Woodpecker tattoo. The possibilities of this connection are myriad and intriguing, and it's also a pretty funny gag.

If your point is to show how we are all connected, I think showing some of the strangeness and the absurdity of those connections would be part of that truth, but sadly this whole birthmark business is treated very seriously in "Cloud Atlas." So much so that one reveal of the birthmark is treated like an astounding moment, which I suppose it is as the person with the birthmark is someone who wasn't, technically, born, which brings up a number of questions, none of which really matter.

What's important, though, is that identity is fluid and that we're all connected, right? I mean, that's why they did all that crazy race and gender casting, right? Because it doesn't really matter what your skin type is or what bits you have, we all have the potential to be absolutely anything!

Except a bad guy, of course. If you're a bad guy, you MUST be a white male.

One of the many things that's irritated me about the Wachowskis is their predilection towards the noble savage/magical negro trope. It plays throughout much of their work, but nowhere moreso than in "Cloud Atlas." In a movie that hits so hard on identity politics it really doubles down on the heroic, selfless, wise minority versus the cruel, oppressive, idiotic White Devil that even when the bad guys in the film must, by necessity, NOT be white men, as with the villainous Nurse Ratched character in the Cavendish section or the emotionless Korean government stooges in the Neo Seoul section, they're still ALWAYS played by white male actors. And with so much race and gender switching going on, they even had the opportunity to dress up one of their Asian, black or female actors to play one of the many villains. Nope. Always white. Always male.

This shows a sincere lack of conviction in their thesis, and exposes the film to be not a philosophical or intellectual examination on the essence of humanity, but a shallow, pandering feint towards multi-cultural "hipness" crossed with a healthy dosing of white liberal guilt.

Which is a shame, because here and there the Wachowskis (and Tom Tykwer, who I've pretty much treated as a tourist here but should probably assign some amount of responsibility to as well) create some fun, diverting scenes, characters and images.

It's also a shame that apparently their next film will have them returning to the Matrix universe again, the last time the world bought into their intellectual shell game, and not doing something more along the lines of Speed Racer, where their kinetic flare and imagination found its most comfortable home yet.

But that's just my opinion, and alas, I am a privileged white male with nary a comet birthmark in sight, so I'm probably horribly, horribly wrong.

NetFlix Review #27: Killshot

The sad yet simple truth is this, my friends: by and large, villains are more interesting. They're mysterious, we want to know more about them. Of course we know why the hero wants to pull babies out of a burning orphanage, but why, WHY did that cackling madman set it on fire to begin with?? This issue hangs over Killshot like a cloud. The movie is filled with actors I enjoy, such as Tom Jane, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Rosario Dawson, Hal Holbrook. It also has Diane Lane in it, who I can generally take or leave. But all these people may as well just be window dressing, as Mickey Rourke towers over the proceedings as the cool-as-a-cucumber bad guy Armand "The Blackbird" Degas.

Even without the villain rule, the movie is bound to be ruled by Mickey Rourke, an actor I've loved for years. He's an undeniable presence, and a role like this suits him perfectly. Watching Blackbird amble through small Canadian towns quietly, coldly wreaking havoc isn't a terrible way to spend a couple hours. The problem is, the movie doesn't want us to just spend time with Blackbird. Blackbird's the bad guy, you see. That means we have to have good guys. So in come Tom Jane and Diane Lane, a couple going through a trial separation who have a run-in with Blackbird and escape alive, something Blackbird doesn't like to let happen. Whenever the movie focuses on the Jane/Lane couple, things grind to a halt. Which is a shame, as Tom Jane is an actor I continue to root for, although true stardom keeps juuuust eluding him.

The lack of coherence or interest in the relationship plot is interesting, as the director of this movie, John Madden (no, not THAT John Madden. If ONLY...) has previously done mostly relationship movies, like Captain Corelli's Mandolin, Proof and Shakespeare in Love. So it's weird that the relationship here felt so odd. A good deal of it is certainly the writing. Jane's character is a bland, good-natured rube and Lane's character obviously still loves him, but wants a separation, but gives us no actual reason for wanting to be separated. Tom Jane is a big, handsome man who comes over and fixes up her house even after she's kicked him out, only wants to be with her and is even trying to get new work so he can be the man he wants her to be. What, exactly, is her problem?

Joseph Gordon-Levitt fares much better as a wild youngun' who The Blackbird takes under his wing (har har) because he reminds The Blackbird of his younger brother, who The Blackbird accidently killed a job gone wrong. Gordon-Levitt is easily one of the most entertaining and gifted actors of his generation. He's obviously having fun here, and whenever he's onscreen things get instantly better. He's also well-matched with Rourke, as Rourke's stoicism and Gordon-Levitt's manicness play well off each other. Plus, he tears a moose head off a wall, which is undeniably delightful.

The issue here, which spans the movie entire, is that it's a great set-up with no payoff. The way Gordon-Levitt and Rourke's relationship ends should be a great moment, but instead just kind of sits there onscreen because nothing really builds up to it. There's no reason for what happens to happen at that moment rather than any other moment because both characters are acting as they always act, in a situation just like situations they'd been in before. A similar moment happens in another Elmore Leonard adaptation, Jackie Brown, but it's handled much more deftly, and the moment really sings in that movie. There's a bit where Jane's character goes to get a new job like his wife wants him to, and he figures why not try and get a job at his wife's real estate company? It's a charmingly dunderheaded move with some good comic potential, but only results in Lane flatly laying it out, "You came looking for a job at MY company?" There's also a bit later in the movie where the couple are hiding out in the Witness Protection Program and while out with new friends Jane accidently calls Lane by her old name. He covers by saying her mother called her that name, Carmen, because she was such a good singer. This sets up a great deal of potential that is dispatched with quickly by Lane saying she won't sing and then that's the end of it. It's not that the movie is bad, it just doesn't even attempt any steps towards being great.

What it does do well, though, is quiet menace. The scenes where Rourke returns home to the Indian Reservation of his youth are pretty great. Everyone holds him at a distance, and its not certain whether they know what he does for a living, or whether they all remember something from his past that led him there. He shows up, and everyone is on edge. Rourke also has great moments with Gordon-Levitt's girlfriend, played by Rosario Dawson. Again, his motives and their relationship are unclear, and it keeps a taut, quiet tension throughout every scene.

The long and short of it is that it's a well-made, workmanlike thriller. There's no real surprises in the plotting, nor any exceptionally bravura moments, but the cast is roundly good, Rourke is great as always and Joseph Gordon-Levitt continues to shine. It's better than your average DTV (or I suppose DTD now, as nothing really goes directly to video anymore, does it?), but I can also see why it didn't get a theatrical release.

NetFlix Review #26: Bad Lieutenant

Martin Scorsese once said that he had only two interests in life, religion and the movies. There's a reason I frequently call the man my favorite director of all time - we have much in common. I find hardly anything in this great big world more interesting than movies or religion. So when a movie wrestles with religion, really and truly grapples with it, I sit up and take notice.

On a very surface level it seems ridiculous to say that Bad Lieutenant is a religious movie. It's rated NC-17. The movie is most famous for Harvey Keitel showing his junk. There's rape, drug use, violence, all manner of nastiness. However, below the surface the movie runs on pure religious dogma, and its question to us is this: what does it truly mean to forgive, both others and ourselves? How does God forgive?

Keitel plays The Lieutenant, one who is bad in pretty much every sense of the word. He's a drug addict, a gambler, he buys women, mistreats his family, uses his job to extort young women. Abel Ferrara, the movie's director, tips the scales nearly to the point of absurdity to make sure we see Keitel's lieutenant for the scum that he is. He doesn't want us to feel that the lieutenant is merely a rake who doesn't play by the book and goes outside the lines sometimes. He wants us to see that this man is a very, very bad lieutenant, indeed. Things begin to change when a nun is raped by a couple of teens. Slowly remorse begins to creep into the lieutenant's life, and as he begins to re-evaluate his life, it begins unraveling at the seems.

For all that Ferrara hits the button-pushing pretty hard, he also knows just how to throw in an image or a connection that cleverly undermines the shock of what you're seeing by forcing you to re-evaluate how you see it. What is important is the follow-through.Take, for instance, the rape scene. Intercut with the violence is a scene of the crucifixion. This could easily be written of as simple shock value, but knowing where the movie goes, Ferrrara seems to be showing us that this is what the nun was thinking of during this violating act. Later in the film the nun forgives her assailants, as that's what Jesus would have done. Keitel finds this unimaginable, but this woman believes that the pain she felt was nothing compared to the pain Christ felt, and if Christ could forgive those who killed him, she can forgive those who raped her. It's an extraordinarily difficult thing to grapple with, and Ferrara hits it head on. When Keitel goes to the hospital to check in on the nun, he walks in on her being examined. The nun is revealed to be an incredibly beautiful woman, and as Keitel leers at her unseen from behind the door Ferrara is putting him in a similar position to the rapists. Later we sense that Keitel has felt that connection as well. His rage against the nun for not turning in her assailants becomes rage towards himself for being like them, not only in his sinful ways, but in that he too has gone unpunished.

Keitel's performance is, at the very least, fearless. His actual acting abilities have, at times, been a subject of much heated debate, but he certainly never phones it in. His role here is stunning. There is, of course, the infamous nude scene, which gets much more attention for Keitel's schlong than it does for its religious implications - a naked man in a state of "ecstacy" with his arms in the position of the cross. He's also not just naked physically, but emotionally. He staggers around, mewling and crying like a child. He knows there's something wrong, that he has something to answer for, but he cannot find those answers. He is lost, naked and bestial, yet even in that state, as he cries out to heaven, a part of him echoes the image of a dying Christ. It is, in its way, extraordinarily powerful stuff. Near the end of the movie, when the lieutenant is doing what he now thinks is right, something which goes against every instinct in his body, Keitel plays the character with an actual, audible wincing moan between lines, as though he is physically wracked with pain at what he's doing. It's an extreme, daring choice, unglamorous, uncool and grating, but to my mind fascinating and well within the aesthetic of the film.

It's also intriguing to watch Ferrara defy expectations throughout the movie. When you hear the plot description for Bad Lieutenant you think of the gritty 70s exploitation flicks or, at the heighth of the artistic ladder, Scorsese's brilliant early work like Mean Streets and Taxi Driver. However, Ferrara denies us the sexy anti-hero, titillation and violent catharsis we've come to associate with those movies. Keitel's lieutenant isn't really daring, dangerous or misunderstood. He's just... bad. Bad at his job, bad with his family, a bad person in total. The "sex" scenes provide none of the naughty vouyerism of some other "gritty" movies. The rape is nasty and punctuated by images of Jesus on the cross. When Keitel pulls over two girls driving without a license and uses his power as a police officer to sexually exploit them Ferrara doesn't ramp up the raunch, but instead makes it long, drawn out and painful. It doesn't feel "sleazy dirty," it feels horribly, uncomfortably real. As in the nun rape scene, Ferrara uses a distancing technique which also implicates the viewer - Keitel doesn't actually have sex with the girls, but forces one girl to show him her bottom and has the other mime oral sex while he masturbates. He's not physically doing anything to them, he's watching them - just like the audience is.

Also, not to get into heavy spoilerage, but I like the way the end of the film sets up a big, Taxi Driver-esque confrontation, and then completely pulls the rug out from under it. It's a move that is both ballsy and deflating, which kind of sums up the whole movie. As we were discussing the movie afterwords Emily said, and I agreed, that it's a much more enjoyable movie to discuss than to watch. In between the bravura moments are long stretches filled with slow drug scenes, shots of Keitel walking around places and also listening to baseball games on the radio. While there are certainly a few wonderful elements to be found in those scenes (I love that Keitel unceasingly bets against his home team. Talk about self-loathing!), and you have to respect Ferrara's DIY, on-the-cheap approach, they don't liven up the already dour proceedings. It's definitely a fascinating flick, but I highly recommend watching it with someone you can chat with about it later. You'll want to.

NetFlix Review #25: Under the Cherry Moon

Well, I'm going to make some enemies here, so let's be done with it.

First, and most ashamedly, I'm not huge on Prince. I like a few of his songs, but overall I find him and a lot of his work a headache-inducing combination of a pretentious artist provocateur and that girl from high school who was waaaaay too into musical theater. And frankly, that dualism has never been more apparent than in Under the Cherry Moon, a movie I honestly cannot imagine anyone taking seriously, even as a joke.

In the movie Prince plays a gigolo in the French Riviera. Prince's Christopher Tracy and his brother/friend/partner/lover/unsure Tricky (Jerome Benton, one of Prince's musicians) hop from woman to woman wooing, seducing, grifting and then leaving. However, Christopher finds that something changes when he goes after a young heiress Mary Sharon, played by Kristin Scott Thomas. Has love finally come to hustler Christopher Tracy?

Yes, but not from Kristin Scott Thomas. One of the film's many problems is that the love triangle between Christopher, Tricky and Mary seems irrelevant because Mary cannot seem to illicit half the passion from Christopher or Tricky that they lather on each other. Some people seem to believe that this was Prince wanting to play up the questions about his sexuality, but even if that is so it's done at great expense to the film. I don't know if I've ever seen a gayer couple in cinema, and I've seen Brokeback Mountain, Shortbus AND Top Gun.

The attraction to Mary seems perfunctory, which is astounding because Kristin Scott Thomas looks GORGEOUS and acts with the energy and tenaciousness of an extraordinary talent being given her first chance to shine, which is exactly what was happening. How could you NOT be attracted to her? And yet I don't believe for a second that either Christopher or Tricky would give up what they claim they would to be with her. It also doesn't help that Christopher and Mary never meet as equals, never actually get to know each other in any meaningful way. They fall in love the way 12-year-olds do. She's the smoking hot prettiest girl in the room, he's the loudmouth bad boy who upsets daddy, they drive around in a cool car that has a license plate that says "LOVE" and listen to music and sometimes they totally call each other on the phone and don't even talk they just lay in bed and listen to each other can you believe it that's so romantic OMG it's just like a moooooviiieeeee!!!!!! Perhaps one of the greatest annoyances here is that I find it extraordinarily difficult to believe that Prince would be infatuated with anyone nearly as much as he's infatuated with Prince.

Nothing here feels real or earnest, which is problematic when you're making a love story. Nothing is based off of actual, observed human behavior, everything is gutted from other movies and bought wholesale, then cobbled together. A movie can be as fantastical as it wants, but it has to be based around real characters interacting in a somewhat believable way. There must be an internal reality. The only internal reality within the film is that Prince is FABULOUS!!! To the movie's credit, it does somewhat sustain that reality, and I suppose your level of enjoyment comes with how far you feel that reality can take you. It would have been a fine music video, but for an hour and a half, it's overplayed, overstayed and underwhelming.

I'll give the film credit where it's due. The movie looks fantastic. Michael Ballhaus did the cinematography, and his long list of credits, including a number of Scorsese films and Francis Ford Coppola's (one of my favorite visual movies) speak to a talent hefty enough to make a movie look better than it has any right to. Kristin Scott Thomas is brilliant to watch. She's funny, flirty and dead sexy. She's since poo-pooed the movie, proclaiming it pretty much garbage, which furthers my belief that she's a sensible, intelligent woman. And I will say that the music is enjoyable, especially Prince's possible high water mark, "Kiss."

I will also concede that I found the movie hypnotically watchable. Emily will disagree vehemently, as she got so bored she stopped watching about halfway through, but I found the whole thing oddly mind-boggling. Who greenlit this movie? What do the people who love it see in it? How does Prince exude such a heightened air of sexuality while still also seeming entirely and completely sexless? What would the movie have looked like if Prince hadn't fired the original director and took over directing duties himself? What could it possibly be like to act opposite Prince, especially for Kristin Scott Thomas? It's definitely not much like anything else you've ever seen, for good and for ill.

So I call out to you, Prince fanatics! Why, WHY is this movie cinematic gold? Do I simply lack the Prince gene? I have, inconceivably enough, never seen Purple Rain, is it possible I'd like it more? Weigh in!

(Spoiler From the Future: Saw Purple Rain at a friends house. Better than Under the Cherry Moon, but not by much. Sorry, Prince.)

NetFlix Review #24: Mr. Brooks

NetFlix Review #24: Mr. Brooks

I'd been intrigued to see this for a while, as I'd heard from many reputable sources that it was bugnuts insane. Was I disappointed? Well, let's list a few things that appear in this film: Kevin Costner as a fuddy duddy daddy who is also a serial killer with a distancing psychotic break in the form of William Hurt. Costner has a daughter who may have inherited his "serial killer" gene. Dane Cook is a photographer who snaps Costner in the midst of a murder and blackmails him not for money, but to follow him around on a kill, basically like a ride-a-long with a sheriff, but with a serial murderer. Demi Moore is a tough-as-nails cop who is also set to inherit millions of dollars. She's also going through a divorce. AND chasing ANOTHER serial killer. So the movie does indeed have a lot going for it. But is it good?

Well, it kind of depends on your definition of good. While all of that insanity previously listed does occur in the film, it also never flies off the rails into total crazytown. Which is... good? Everything I want to praise the movie for, I also hold against it. Costner actually gives an interesting, underplayed performance, really trying to find a way to bring together the daffy affability of a man-of-the-year, doting father and good husband with a man who has committed compulsory murder for decades. William Hurt definitely chews scenery as usual, but given his character and the story around him, really not as much as he could have. Dane Cook gets his super-sleeze down pretty well. Demi Moore plays her icy detective in her very 90s thriller style, which I kind of dig, I'm not going to lie. Basically, everyone's acting very professional, and I kept praying for someone to go bonzo.

The movie's main problem, outside of no one going insane to please my personal whims, is that it's packing in way, way, WAY too much stuff. Any one of the five or six major threads of the movie could have carried its own feature. Particularly ill-served is the plotline that posed the most interesting questions, the daughter who seems to have possibly inherited daddy's penchant for killing people. When Costner finds out about daddy's little criminal liability he becomes conflicted about whether to let her go to jail, to try and help her, does he confront her about it or hope that this isn't what it looks like? There's room here to explore how behavior is passed from generation to generation, the trauma of parents letting go of their children, the boundaries of familial love and responsibility, on and on. However, the few of these issues that actually get addressed in the film get paid lip service, and the whole setup is used largely as just another link the chain of events. Costner's character is given a lot of fun, interesting touches (I particularly like how he attends AA meetings when the urge to kill comes back to him because, well, there's unfortunately no Serial Killer's Anonymous) but nothing seems to go much of anywhere. They've set up some interesting dilemmas that could turn into fascinating character examinations, but instead fall back into the old thriller playground of "how's he going to get out of this mess?!?"

Not that some of that isn't entertaining. I enjoyed Costner's cat-and-mouse-esque game with Dane Cook, and the payoff, although fairly predictable, is a fun bit. It would have been nice if Cook hadn't simply been a base-level cretin, though. If Costner's serial-killer can have some dimensions, why not the serial-killer-wannabe? What if Costner's dilemma wasn't simply how to get out of this quandary, but how to deal with someone he may see parts of himself in? I suppose that's why we ALSO have the daughter character, but what if we just collapsed some of these things together? Maybe? Movie? What's that? You're still going to be five movies at the same time? Fair enough.

The team behind the writing and directing of the movie is also the team behind such fair as Jungle 2 Jungle, Cutthroat Island, Stand By Me and Starman. I watched the eight minute feature on the DVD about the writing of the movie (how could I not?) and things began to make a bit more sense when the duo began talking about how they were a bit tired of writing family fare and decided they wanted to make an "adult" movie, and what's more adult than serial murder? The movie does have a feel of coming from people who had been playing in the kiddie pool for a while trying out the adult toys. For instance, in the murder where Dane Cook's character spots Costner's, Costner comes in on two people having sex and shoots them both in the head. At a couple of points throughout the movie they flash back to this scene, but most particularly the moment in the scene where you see the woman, large breasts a-wobbling, screaming and then the splatter of gore as the bullet enters her head. It's gratuitious the first time you see it, but we are making a movie about a serial killer, so all right. But then the third or fourth time you see it you really have to start wondering. However, knowing what I know now about the production team I can see them thinking, "Oh man, this is WILD! This is so NASTY! We've NEVER done anything like this before! Show it again! Show it again! People won't BELIEVE it!" They're like a kid finding a condom in their parents' bedroom and showing it ecstatically to everyone at school. "Do you know what THIS IS????" This might also explain the cramming of every idea they appeared to have had into the movie, and why everything, outside of frequent cutaways to a naked woman being shot, is so restrained. "We're making an ADULT movie, so let's rain it in, people. We don't want things to get too wacky, wacky is for kids, and this may be the only chance we get to really go dark, so let's do it right."

This is all speculation, of course, but I cannot help it, as one of the main conundrums of this really odd movie is, frankly, why isn't it weirder? Has anyone else seen this? I earnestly would love to hear some thoughts on this one. Also, anyone beside me think this movie should have ended about 45 seconds earlier? Those of you who have seen it will know what I'm talking about. Weigh in!

NetFlix Review #23: Madhouse (a.k.a. There Was a Little Girl)

NetFlix Review #23: Madhouse (a.k.a. There was a Little Girl)

Aaah, the glories of the giallo movies. For those not in the know, "giallo" as a film term refers to a very specific kind of thriller/horror film made in Italy that really came into its own in the 60s and 70s. They are characterized by nonsense plotting, beautiful scenery, even more beautiful women, heaps of gore, extreme stylization, unusual rock-infused soundtracks and a completely bizarre understanding of "psychology." They, along with some super-sexy 60s and 70s erotic films like Radley Metzger used to make, seem to me like the pinnacle of trashy class. Madhouse was recommended to me by the trashy, classy Paul Busetti as a giallo set in Savannah, GA. Having lived in Georgia for a while and being a huge fan of Southern Gothic, I thought this sounded like a potentially sweet little number.

The film is more of a mixed bag. It certainly has a lot of beautiful photography, and the lead actress, in apparently the only movie she ever made, ain't too bad to look at. The plot is pretty typical giallo. A woman, Julia, has an evil twin sister named Mary who is locked away in an insane asylum. Their birthday is approaching, and the girls' uncle, a priest named Father James, wants to reconcile the two girls. This doesn't look likely, however, as the insane sister has also recently suffered a horribly disfiguring accident that has ruined her face, which, as you can imagine, doesn't help her psyche all that much. Mary escapes and Julia's friends and associates start turning up dead. Isn't. That. STRANGE?

The director of this film, Ovidio G. Assonitis, is a well-known and, in an odd way, respected hack. He did a famous rip-off of The Exorcist that was one of the highest-grossing horror films ever in Italy, as well as rip-offs of Jaws and other big horror films of the time. In a way Madhouse feels like a giallo rip-off, even though the guy has serious Italian film-industry cred. It gets a lot of the beats down, but lacks the gothic excesses of Bava or the completely off the wall visual playfulness of my personal favorite, Dario Argento. Most disappointing to me, it doesn't make much use of its southern setting. Savannah has a great atmosphere to it, and should have greatly underlined the mood of the piece. I'm a fan of both The Gift and Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, which were both filmed in and around Savannah and used the city to great effect. Madhouse sets most of its action in Julia's house, which, although it is certainly a very Savannah-style home, may not be taking full advantage of the tools at your disposal.

The movie also has a reputation for being one of the "video nasties," films that were banned in Britain for being vulgar, violent and obscene. It's funny watching it today, where the film could practically get a PG rating if you took out a couple moments of violence. My how the times have changed. As for those moments of violence, the bread and butter of any good giallo flick, the film is pretty tame until the very end, where you get a moment involving a dog which is both abhorrently grotesque and kind of hilarious, and the final birthday party, which I do have to give the film some credit for. One of the issues with giallos is that sometimes they're simply too art-directed, too pretty, to actually be scary. Of course, that's really only a problem if you want to be scared. The party is very well-designed. Austere and creepy, owing a little bit to the dinner scene in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, but it looks a lot better. There's also a well-constructed moment where there is a rise in the tension and madness of the scene, and then someone is murdered and both the insane frivolity and the murdered party fall dead into Julia's lap. It's a solid bit, and one that someone should steal and put into a better film.

There are all sorts of "spoilers" I could go into to further discuss the movie, but there's not that much point. You'll probably guess most of them from the very get-go, or more to the point most of you will probably never even consider watching this in the first place, but why not keep them hidden? It's a moderately successful giallo, so if you're a fan of the genre you could certainly give it a go.

There is one thing the film made me want to ask all of you out there in readerland: Has there ever been an instance in all of cinema where a villian singing a song, especially as a sign of them being craaaazy, that has actually been scary? The baddie in this movie does it, and it's a trope I always find much more annoying than horrifying. Especially if it's sung by a little child. It always feels like something is trying far far too hard to be scary instead of actually scaring me. I think one of the only times I've ever found this effective is the "1, 2, Freddy's Coming for You" song from Nightmare on Elm Street, and I think it works because it's set up within the world of the movie. Like "Ring Around the Rosie" it's a rhyme based off actual horrific events that becomes diluted into a children's song. There's something that feels much more organic about that. Oh, and Dan Aykroyd's rendition of "She'll be Coming 'Round the Mountain" in Grosse Pointe Blank, because that actually seems very in character as something he'd do to unnerve someone, and it's pretty insane. Any others? Or perhaps, what are your WORST examples of people using this trope terribly? This movie's pretty bad, especially as it goes on for SO LONG, but one of my favorite examples of this going tits up is in Enduring Love, when Rhys Ifans sings "God Only Knows What I'd Be Without You" to Daniel Craig as a signifier that he be craaaazy, y'all! It made me embarrassed for everyone involved.

NEtFlix Review #22: 12 Rounds

Be careful who you steal from. If this isn't one of the primary rules of scriptwriting, it should be. All screenwriters steal, to one degree or another, because they've all been inspired by other films. This is inevitable. However, how you steal, and from whom you steal, is extremely important. For instance, if you're, say, making an action film starring a charmingly wooden professional wrestler as its lead, you may certainly want to look at movies like Die Hard and Speed to get some ideas about what you're going to do. You do not, however, want to lift things directly from those movies, as those movies are classics in the genre that people like me have seen far, far too many times. If your movie is all dressed up like Die Hard, but doesn't have John McClane battling against Hans Gruber, all your going to do is make me annoyed that I'm not actually watching Die Hard.

I know there's only so many ways you can blow things up or make a chase scene or have a villain toy with a hero, but this is honestly bordering on plagiarism. It's Die Hard, Die Hard 3 and Speed in a blender. I can quote all three of those films, they are archetypes, they are the gold standard. You crib from them, I'm going to notice.

Which is all a shame, because I find John Cena, although certainly a wrestler more than an actor, a charming screen presence. Aidan Gillen continues the streak of alums from The Wire finding nothing worth their talents after the show. Even Renny Harlin has done much better work. It feels like The Marine made some decent money, so they threw something together. Everything seems lackadasical and shrugginly assembled. The action scenes don't pop, the threatsdon't feel terribly urgent and the hero doesn't seem to ever be too overwhelmed or outgunned. It's paint-by-numbers action filmmaking.

There's really not much to say because the movie brings nothing to the table. The major point of enjoyment is hearing John Cena's voice crack as he tries to portray "distress" by yelling a lot while driving a fire truck.

I remember being curious to see The Marine, as I do like John Cena, but also it has Robert Patrick as the bad guy, and perhaps one of the things that might have really boosted this film would have been a decent threat. The only moment Gillen actually gets a personality is a hilariously tacked on bit where he butts into a chess game to show that he is nefarious AND clever! Stratgery! Patrick has always been great at chewing scenery and throwing some fun into anything he shows up in. Anyone seen both movies? Anyone attest to a variance in quality? I'm mildly curious!

Regardless, here's my wacky movie reviewer quip to polish us off: 12 Rounds? One was enough for me, thanks!

ZING!

I'm a genius.

NetFlix Review #21: White Men Can't Jump

In the last review for Role Models "charm" and "humor" became a central point of conversation. It's going to come up again here, because this is a movie that uses a foundation of charm and humor to build an actual story and show us something interesting, something we've never quite seen before.

I've been curious to see this movie for a long time for one very odd reason: rumor has it this is one of Stanley Kubrick's favorite films. I'm not a zealous Kubrick devotee like some people I know (Charlie Wilson), but I think the man frequently touched genius. He's certainly a fascinating dude in many ways, but the concept that this was one of his favorites kind of blows my mind. What did he see in it?

Now having seen the movie, I think I've got a possible explanation. Kubrick was notorious for having his films be cold, distant and controlling. He was a renowned micro-manager and a complete obsessive. His movies are filled with stunning detail, gorgeous production and tightly controlled technical tours des forces. He also seemed to be someone fascinated in the worlds beyond him, and what must have felt more beyond him as a filmmaker than the kind of loose, improvisational style. Also, as an exceptional formalist he must have been intrigued by the film's unusual construction. I could see him finding it an amusing puzzle of a movie, as that it certainly is.

It is noteworthy how unusual the film's structure is. First of all, it's a con movie that obeys none of the rules of the con movies - the big con happens in the middle of the movie, the possible betrayal turns out to be a real betrayal, and doesn't lead to former partners becoming enemies, but to a very anti-climactic forgive and forget. The whole film is structured along similar lines, with every moment that should be a grand denouement - the competition, the Jeopardy game, the match against the old pros - is dramatically undercut. The form is the message, though, as writer/director Ron Shelton understands that in the dodge, just like in sports in general, there is no one big score or one big game that becomes a defining moment. After every championship starts another season, and after every con is another hustle. For people who take on something so challenging, so completely engrossing, it only ends when the body gives out, when they simply and absolutely cannot win any longer.

Shelton understands sports, and the compulsions of the people who work hard enough at them to play professionally. He is, after all, the man behind Bull Durham, regarded by many to be one of the greatest sports movies of all time. He also did Blue Chips, Tin Cup and the, in my opinion, unfairly maligned and pretty fantastic Cobb. Shelton's grasp on sports comes from having lived it, he played five seasons of baseball on a triple-a farm team, and he uses that understanding to put across on screen a truth that few sports movies ever touch on - for these men, saying baseball or basketball or golf is a "way of life" is indeed true, and that truth has some rather serious ramifications.

Just look at the way Woody Harrelson's character is constantly chiding Wesley Snipes that he would rather look good and lose than look bad and win. Snipes' character is definitely a showboat, but it's Snipes who cons Harrelson by playing poorly and looking bad only to have actually won by fixing the game, meanwhile it's Harrelson who loses money on trying to prove the movie's title false, a vain attempt to make himself look better than he is. The question the movie inherently brings up is how does one define "winning," not just in sports but in life? Everyone in the movie is, to some degree, a winner. Snipes and Harrelson are a fairly unstoppable team on the court, so much so that Shelton wisely never puts much dramatic stock in whether or not they'll actually win. Rosie Perez's character sweeps Jeopardy, but of course she would. The question is how will they handle their winnings? It's also to Shelton's credit that he doesn't make anyone a simple dichotemy - great on the court, terrible at home. Snipes is trying to build a legitimate business aside from his hustling so he can move his family out of their bad neighborhood apartment into a house. Harrelson and Perez are seen as having a very warm and loving relationship. Their scenes together have an easy comfort to them that makes it feel like a very real relationship, not a gimmicky movie one. Snipes marriage, although we see less of it, is similarly healthy and nurtured. These are men with a lot of skill and charisma who have found great partners and are fighting to make their way. So why do they still feel like, and occasionally act like, losers?

Having mentioned the women, I'd like to draw particular attention to them again here, as here is another place where Shelton raises this movie far above standard fare. Usually in sports movies you get two kinds of women, the loyal wife of a respectable gamesman, or the practically faceless arm candy of the womanizing player. Both roles are largely insubstantial and only serve as props for the male characters. Here both women are their own people. In fact, one of the best scenes in the film is the kitchen confrontation between Perez and Snipes' wife, played by Tyra Ferrell. Both women have their own wants and desires, and they neither placate their men with saintly patience, nor are they shrews. You can see why both men, competitive and demanding, would choose these women - by all appearances they are probably the best to be found.

Outside of all of this, the movie is also ridiculously entertaining. Snipes and Harrelson are a joy to watch. They layer their characters with an almost effortless ease. Snipes' transitions between loudmouth street hustler, gentle family man and professional businessman are so fluid you don't even see it happen. Harrelson exudes such charisma, such sheer joy and goofy amiability that it becomes disheartening to reflect on how he missed becoming an a-list star.

It's interesting writing this review after Role Models, as this is a movie that could have easily been a paint-by-numbers sports comedy, but Shelton took the time to craft a film that defies expectations and surprises the audience with its intelligent yet playful ruminations on the games men play. Even the movie's only slight misstep, a subplot about criminals Harrelson and Perez owe money to, pays off with a solid undercutting of expectations. It's a film that wins, while also looking exceptionally good. I get it now, Kubrick. Well played.

NetFlix Review #20: Role Models

Many many moons ago there was a sketch comedy team called The State. They were a mystery to me. I never saw the show, but my friends quoted me every sketch verbatim. I bought their book, State by State with The State, and considered it a comedy treasure. In college I saw Wet Hot American Summer and adored it. But then... something happened. Some of them did Reno: 911, which I've never found funny. Then there was Stella, which I also didn't find funny. I sat through The Ten and watched a ton of people I usually find hilarious fall completely flat. There was Wainy Days, The Baxter, Taxi, The Pacifier, Herby: Fully Loaded, Balls of Fury, Diggers, Run Fatboy Run, Night at the Museum and every single time Michael Ian Black showed up on any I Love the ____ show - None of them all that funny. What the hell happened? The State has just been released on DVD after a long struggle to get it out, and although I'm curious to see this show I heard so much about throughout my formative years, part of me can't help but wonder - was it just a "you had to be there" kind of cultural event?

The point of all this being that I never saw Role Models in the theaters, despite many people telling me how funny it was, as I found it so difficult to remember the last time any of these guys had made me really laugh. The final verdict: I was wrong. And yet...

The movie follows two men who push energy drinks, played by Paul Rudd and Sean William Scott. Through highjinks and shenanigans the two are faced with jail time or volunteering at a mentorship program, helping out two kids so dysfunctional they can't keep a mentor for long. Think you know where this is going? You're probably right.

You can't talk about this movie without talking about charm. Paul Rudd and Sean William Scott are, to me, goofy charm machines. I'm sure they're not everyone's cup of tea, but I'm always excited to see them on-screen. And, in a way, this is kind of my issue with the movie.

It's hard to be funny, really and truly funny. If you doubt this, simply watch any sitcom on ABC, or anything on Comedy Central that isn't The Daily Show, The Colbert Report or South Park. If you are a funny person, people seem to believe, especially in Hollywood, that the humor you produce isn't through hard work, diligence, the scrutiny of the world around you and the study of how to build and execute a joke, but instead it is secreted out of your pores like some sort of hormone, a natural byproduct of your wacky genetic make-up. Consequently they believe that they can simply insert you into whatever bare-bones, bottom-level project they've got lying around on the cheap and you'll be able to make it funny because, you know, you're a funny dude. This is how movies like Semi-Pro or Night at the Museum get made. And, in a sense, this is how a movie like Role Models gets made.

I feel like I'm being a bit of a grumpy gus here, because I did really enjoy myself during the movie, but as I think back over it I do feel like I have to mention that most of the stuff I liked about it seem to be no fault of the movie itself, but just watching Rudd and Scott riff off each other. Whenever I think back on the jokes that are actually constructed into the film there are only a couple that have any real zing to them. For instance, the character of Martin Gary, the overly-earnest serial volunteer at the organization Scott and Rudd are sentenced to. Outside of his "Wings" joke, nothing he does is particularly funny, nor does he set up any great jokes. He's a funny idea, but that's about as far as they got. The same can be said for Jane Lynch's character. I feel like I can hear the entire conversation that led up to her character in my head: "How are we going to make the head of this Big Brothers-type foundation funny?" "How about if she runs this charity, but she used to be a total coke whore, and she brings that up all the time?" "Awesome. Ok, next character." And that's it. They're smart enough to hire someone like Jane Lynch, a pro at drawing the funny out of the smallest of appearances, but even then there's not that much to it. And poor Elizabeth Banks is particularly wasted. As I keep reading article after article about how Judd Apatow is a terrible, woman-hating, vagina-loathing, estrogen-fearing monster, it's interesting no one has mentioned any of these The State people. Look at the crappy, under-written roles they keep doling out to actresses, like Elizabeth Banks in both this movie and The Baxter, or Carla Gugino in Night at the Museum, or Thandie Newton in Run Fatboy, or any of the ridiculous female roles in Diggers. But I digress.

The point of all this being that it's kind of hard for me to say this is a "good movie," as it's largely some fun performances tacked onto a kind of crappy, really transparent story. WILL the two rogues end up liking their assigned kids? WILL they go to jail? WILL the climax to the movie have anything to do with the LARPing they show throughout the movie? WILL Banks and Rudd get together in the end? WILL Rudd and Scott become true friends? It's not that I need to necessarily be surprised by any of this, but it's all just kind of lazy. If you're hanging your story on such a lazy plot, you've got to come up with some pretty exceptional jokes or set-pieces to offset the predictability of the story. The Marx Brothers basically made the same movie over and over and over again, but they were constantly challenging themselves to come up with something bigger, wackier, zanier than what they'd done before. That sense of really pushing to find something new is what I feel is missing from many of these movies. It just seems like they're running down a checklist of things that are funny. Little black kid who cusses? Check. Uptight white woman who talks about crazy drugs? Check. LARPing? Check. People dressing like Kiss? Check. It's that laziness of "you guys are funny, so just, you know, be wacky!" that irritates me.

But like I said, I feel like this is very curmudgeonly, as I did laugh and laugh often during the movie. It's a fun flick, but really isn't offering you much more than the chance to see Paul Rudd and Sean William Scott say ridiculous things to each other for an hour and a half. However, there are certainly worse ways to spend an hour and a half.

Again, Night at the Museum, I'm glaring directly at you with vengeful, hate-filled eyes.

NetFlix Review #19: M

Yeah! Here we go! French New Wave is for losers, all the cool kids love German Expressionism!

M is one of those classics that I'm amazed people don't watch or talk about more. It's still creepy, funny, affecting and strange. It's arguably the first real psychological thriller/serial killer movie. It's a parable, an exploration of compulsion, a political screed and a darn fun time.

The movie centers around Peter Lorre's character Hans Beckert, a child murderer plaguing a German city. As children continue to turn up dead the city goes into a panic. The police begin pressing hard against the underworld, the underworld begins to get rueful and angry that they're being equated with a child killer, and the press keeps stirring them both up. As things begin to boil over, everyone begins an all-out manhunt for Beckert.

It's hard to even know where to begin when discussing how great this film is. Let's start with Lorre and the character of Beckert. Long before Spielberg showed his brilliance by keeping the shark hidden, Lang keeps Beckert's true character always out of sight. We see Beckert stalking his victims, hiding from his pursuers , writing a tortured note to the press and, in one particularly affecting scene, making horrible faces in a mirror while the voice-over of another character speculates about his mental state. When his character first appears we're not shown his face, but his shadow cast against a posted announcement of his crimes as he approaches his next victim. Even his crimes are marked by his absence. At the death of poor Elsie, all we see is her abandoned ball rolling away and the balloon Beckert gives her tangled in power lines. Lang is building a monster out of Beckert that lives in shadows, creeps in corners and keeps a low profile. It becomes obvious what needs to be done - the monster must be eliminated, the only question that remains is how.

It is the how that becomes the crux of the picture. It's thrilling to watch the cat-and-mouse games of a whole city hunting down one man, but then, once caught, the "trial" scene tears the rug out from under the viewer. Lorre's performance here at the end is astounding. Everything that they've been hinting at throughout the movie, his psychoses, his anxiety, his fright, it all comes exploding out. But as much as the character is losing control, Lorre is masterful at crafting the rise and fall of each tic, each neuroses. It's a great study of compulsion, of the man who hates himself, but cannot help himself. Lorre brings such pathos and wounded weirdness to what could be a hammy, totally over-the-top cheese-fest, especially given the already heightened, more theatrical acting style of the time, that it truly is a wonder to watch. It's an interesting and telling trivia note that supposedly Lorre actually studied under Sigmund Freud at one point.

In addition to the great monster creation and character study that the central Lorre role brings, the movie also has an extraordinarily weighty political message. The movie was made in Germany during the rise of Nazi party. Lorre was Jewish and Fritz Lang was half-Jewish, so both of them were beginning to feel the heavy hand of persecution and oppression coming down on them. This time was also seeing the rise of the SS, and it's not too hard to see the parallels Lang was drawing between the gang of hoodlums who decide to take justice into their own hands, and Germany's secret police who decided to "uphold" the law by working outside of it. The film manages to have its cake and eat it to by being both overtly about the workings of the police, press and underworld, and then covertly being about the shifting cultural mood and the rise of dangerous fears, scapegoating, mob action and oppression.

In my Pierrot Le Fou review I talked about words that could only come from certain cultures, and I sort of dumped on poor old Germany, land of my heritage!, by calling out schadenfreude as being particularly German. Here's a somewhat nicer word: zeitgeist, literally "the spirit of the times." M is full of the zeitgeist for 1931 Germany. The movie was made while Germany was still in the midst of it's 1930 Great Depression, The Nazis were on the rise and everyone was getting antsy and tensions were rising, but the relevance isn't just in the topical subject matter, it's in the form as well. Lang's use of black and white is beautiful and affecting, making the streets and rooms seem filled with dark pockets where any sort of horror you could imagine might lurk. This was also Lang's first film with sound, and it has the feel of a master crafstmen tinkering with new toys. From Lorre's character whistling Peer Gynte (trivia note: the whistling was actually Lang, as Lorre couldn't whistle!) to the chase through the empty building that is full of echoing footsteps, jackhammers, rustling keys and alarms, there's a fun sense of exploration and play with the sound that is affecting and endearing. The editing is also brilliant, the way Lang cuts back and forth between all levels of society, the businessmen, the police, the underworld and the derelicts, drawing parallels and divergences between them all. It's also a deft move to have Lorre's capture be largely at the hand of the homeless derelicts, because "nobody sees them," as one character notes. There's also the famous way the camera treats Lorre's character in his first and last scenes. Lang puts us in his place. When we see his shadow appear on the posted warning the shadow is coming from the camera/viewer/us. We are the thing causing that shadow. And then, in the final trial scene there are large portions where we see the crowd of criminals from Lorre's character's perspective. Lang puts us on trial facing a hostile and blood-thirsty mob.

That's what I love about this movie and what drives me nuts about Godard - every shot has a beauty to it, and a purpose. Look at the incredible perspective Lang gets out of the shot where the abandoned criminal who has broken through the floor in the building Lorre is hiding in is pulled up to the next level by the police. The shot isn't just stunning to look at, it's a visual representation of one of Lang's central themes, the need for a good, just society to pull the lost and the criminal up out of their holes. It's through this "rescued" criminal that the police eventually find where the underworld gangs have taken Lorre and go to capture him and bring him to actual justice. This is thoughtful filmwork of the highest caliber.

Lang isn't just a technical master, he knows how to play with expectations and audience desire as well. The beginning of the film taunts and horrifies by putting children in mortal danger, then Lang shifts the focus of the film away from the children and towards the monster, where eventually we don't even think about the children anymore, we're so wrapped up in the killer and the manhunt. Then, in the film's haunting coda, we see one of the mothers of a murdered child weep directly into the camera and mourn that justice still will not bring back her child, and that it would behoove us all to take better care of the children. It's an admonition to the audience that has gotten just as wrapped up in "justice" as the mob at the film's end, and also an admonition to Germany at large for taking their eyes off of thoughtful reconstruction and focusing on hateful blaming and destruction. It's a powerful end to an extraordinary and artful film.

NetFlix Review #18: Fitzcarraldo

I'm an avowed Werner Herzog fan. To me, the man makes cinematic magic. His narratives aren't incredibly strong or typically arched, frequently his main characters don't grow or change that much, his shots are long and ponderous, sometimes to a fault, but holy moley. Look at those movies!!! He doesn't really make movies, he makes CINEMA. Although I'm a huge fan, I haven't seen nearly as much of him as I'd like. Fitzcarraldo is one of his big hits, so it's about time I check it out.

It's everything you want from a Herzog movie. His frequent collaborator Klaus Kinski plays the titular character, a man in the wilds of the jungle who, while everyone else is making a fortune running rubber up the river, is trying to build a railroad through the bush and make ice to sell using chemicals. Those near-impossible feats are just his day jobs. His real passion is to build a first-class opera house in the jungle and bring over all the great stars of Europe. He brings his record player with him wherever he goes and plays opera for whoever will listen, and even some who won't. He's indulged in his fancies by Molly, the madame of a local brothel. Though Fitzcarraldo has no money and his efforts are all failures, Molly still gives him large sums of money to follow his passions, because Molly has money to burn. Molly, like the rubber barons, is in the business of exploiting the locals, and business is very, very good.