There's been a lot of talk about the state of current horror films being largely built around meaningless scenes of bodies being torn about. When that talk turns to WHY modern horror has gone in this direction you get a lot of the typical old saws (if you'll pardon the pun) about the decline of society and civility, the loss of morals, the lack of imagination.

None of these arguments ever held much weight for me. Firstly, as much as all these flicks get their jollies off of gore and dismemberment, I don't know that ONE of them has topped some of the prime 70s gore flicks. Secondly, people have been making those same arguments about various incarnations of horror for years, but I think there is something particularly different about this current era of horror film that seperates it from what's come before. I'd never been able to put my finger on it, but now that I've seen The Horsemen, I think I've got a theory:

We're not afraid of anything anymore.

I can hear some of you scoffing from here. "We live in a time of fear!" you're yelling at me through your monitor. "Fear has been the primary emotion of the past decade!" "Two words: 'Fox News'" "I'm afraid RIGHT NOW!"

Yeah yeah yeah, sure, but listen: What are you REALLY afraid of? Honestly? We talk about being afraid of global warming or terrorism or school violence or economic collapse, but are we really afraid of these things? How much do we really think about them? How much do they guide our actions? How much do we take precaution against them? How much do we sacrifice for them? How much do we actively engage with them? OK, OK, I don't mean to jump on you, dear readers, but in the broad cultural sense, I just don't know that there's as much actual FEAR out there as we've been led to believe.

I think there are two things necessary for fear: An element of the unknown and a lack of control. I think nowadays people think we know everything and that we've got stuff pretty much under control. When people talk about things getting "out of control" now, what they really mean is that things aren't going their way, and if people just did what they wanted, everything would be fine. That's not "out of control," that's "out of MY control until I can wrestle that control back."

My good friend Polly Frost is fascinated by disappearance cases. There's more than you'd think, she tells me, mostly young people, mostly women, who are last seen getting into cars with strangers, or walking off drunk into the night by themselves or going down to Mexico and evaporating into the haze of crazy parties. They put up information on public websites detailing where they are, where they'll be, when they're leaving and if they're alone. "These people don't think anything could POSSIBLY happen to them!" she explains to me. They're not afraid. Who is?

This is deadly for horror movies. I don't believe you can make a scary movie unless you yourself are, in some way, scared. Horror movies examine what scares us, and if nothing scares us then all our horror movies can be are remixes of other scare flicks.

And it seems to me, in the same way the prat fall or the fart joke is the baseline for comedy, intense physical bodily harm is the baseline for horror. If you aren't afraid of unknown forces, mental illness, repressed animalistic tendencies, God, predestination, moral failings, karmic retributions, sexual failings, judgment, apocalypse or any of the genre's other many cornerstones upon which the horrors build, really the only thing that's left to you is getting torn apart. In a society that's possibly become narcissistic and onanistic, where nothing of consequence exists outside of the self, the only thing to fear is something explicitly harming the self. Which I suppose may be a lack of imagination, or at least abstract thinking. The only thing these guys can possibly imagine as being horrifying is the fairly unlikely event of getting kidnapped by a deranged killer who enjoys setting up Rube Goldberg death machines for amusement and instruction.

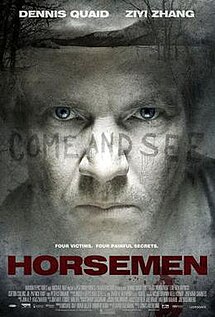

What got me thinking about this regarding the 2009 Jonas Akerlund film "The Horsemen" is the title itself. The titular horsemen are the Biblical four horsemen of the apocalypse. Within the film a group of murders are accompanied with the phrase "Come and see" written around the corpses, pointing the intrepid detective Dennis Quaid to the verse in Revelations detailing the End Times arrival of Death, Famine, Disease and War. What could the killer possibly be thinking, quoting this verse? What kind of connection are they trying to draw to themselves and these scriptural harbingers of doom?

Not much of one. The ending, which I'm going to spoil for you here, as the greatest "spoiling" of all would be to actually watch the garbage, involves Dennis Quaid's son revealing to Quaid that he was part of a collection of kids whose families didn't treat them right, so they've decided to go about viciously murdering them, bringing about the END TIMES of mommies and daddies not doling out enough hugs (or too many, in the case of Ziyi Zhang and her adopted father, a criminally wasted Peter Stormare). There is so much spectacularly wrong with this that I'm not going to go into it in detail, but instead provide a Top Ten list of biggest idiocies:

1) To complain that his dad didn't pay enough attention to him and got all withdrawn after is wife DIED OF CANCER, the son attempts suicide in a fantastically grotesque fashion while having his father watch, which will certainly teach him a lesson and is totally morally equivalent.

2) Also, in doing so he's leaving his younger brother without his support...

3) ...And with a dad who not only lost a wife to cancer, but watched his son hang himself by meathooks and drown in his own blood.

4) Did I mention the kid hangs himself with meathooks? By himself? Which is so impressive, it's impossible.

5) The kid attempts to drown himself through puncturing his lungs, which happens earlier in the film but is executed by someone with medical training. Not some jerky kid. And then he wonders why it isn't working.

6) Also, when did he puncture his lungs? Before or after he hung himself up on meathooks?

7) The kids committing these murders are broadcasting them out to a whole online community of kids who think their parents are jerks and who have all managed to keep this whole thing entirely under their hats and off any FBI watchlist this whole time.

8) Some of the kids kill one of the abusers, some of them kill themselves while making the person who mistreated them watch. For kids who sat together and planned out a bunch of extremely complex and involved murders, it's weird they didn't try to talk their friends out of killing themselves. OR maybe talk the other friend INTO killing theirself. That seems like a weirdly crucial point of the plan to have a disagreement about.

9) The movie actually seems to AGREE with the kid. If we painted him as super-crazy and deranged, that'd be one thing, but the movie seems to be tsk tsking at Quaid's poor parental skills right along with him. Also, the kid's a teenager and at one point complains that Quaid would have realized his plan if he'd ever actually GONE INTO HIS ROOM like a good helicopter parent should, which may be the first time I've ever seen a teenager complain that his parent has given him TOO MUCH privacy.

10) The kid is quoting scripture while doing this, and we see him in church and sort of get a hint that his beloved mother was very religious, which makes this whole course of action seem a little...problematic as far as his belief structure goes.

It's this last point I really want to address. The title of the movie references a Bible verse. We have scenes of the family in church and a few scenes involving Bibles around the house. The main psychopath quotes scripture. But never for one minute do I think anyone in this movie or anyone involved in this movie has any actual Biblical belief, or even any actual interest other than that some verses in Revalations sound real spooky and crap.

I don't think you have to be religious to make religious horror, but I certainly think it helps. And even if you're not, you have to at least take it seriuosly within the world in which it's existing or with the characters who take it seriously enough to act on it. Being religious myself, my love of religious horror is probably what kept me watching this piece of drivel well longer than I should have. I kept hoping, waiting for some moment where they might actually take their own words seriously, where any of this might pay off. Nada.

And then I got to thinking, what horror movies in the last twenty years or so used religion and ACTUALLY took it seriously? The only movie that came to mind was the Exorcism of Emily Rose, which I love. AH, and Red State, which I also kinda loved. But that's about it. I can name you a bunch of movies that use demons, exorcisms, priests and devils, but not a one of them is actually invested in them or what they represent. They aren't even using the religious trappings to SAY anything, or even make it a metaphor for something else. They're just using it as window dressing. They're as scared of or by it as they would be of a rubber spider.

It's not just that they don't find religion scary, I don't think they find teenage alienation or the numbing effects of grief or any of the other possible themes you could pull from the film scary, either. They just think some of the images look cool and that hanging people up from meathooks and self-evisceration is INTENSE and everyone kinda wants to play martyr in front of their parents at some point. Essentially this is the horror movie version of that scene in A Christmas Carol where Ralphie imagines going blind from soap poisoning. And just about as scary.

Why make a horror movie of something you don't find scary? That's like making a comedy full of jokes you don't find funny, or a thriller with set pieces free of intensity or rising action, but I feel like that's pretty much every damn horror movie I see. If I could make one plea to any horror filmmakers out there, I suppose it would be this: Before you try and scare me you should at least be able to scare yourself.